Going back to the old ways

In this series of three audio-visual essays, researcher Ana Lara Heyns shares things she has learnt about the water landscape around Rippon Lea through walking and yarning with Boon Wurrung elder N’arweet Dr Carolyn Briggs AM, and through careful study of archival images, oral histories, maps, newspapers and diaries. In this essay, Ana explains the underground water reticulation system at Rippon Lea installed in 1860 which is an example of sustainable water management ahead of its time; we meet some of the creatures that make Rippon Lea home; and N’arweet considers the role of Rippon Lea for the future.

Ana: Yes.

N'arweet: Oh, my goodness. Gee, how far down does that go?

Justin: Eight or nine metres.

N'arweet: Wow. Quite cold. I can see a bit of water.

Ana: So, from here, what would happen is the pump would pump the water into another set of pipes that would go towards the lake. And then from the lake then, the sets would redirect the water across the garden.

N'arweet: Okay, that’s – yeah, that’s good. People should learn that. So you wouldn’t experience a drought here.

Ana: Well, I think they did a few times.

N’arweet: Did they? Did they experience a drought?

Justin : Well, yeah. I mean, the 1980s drought here was so bad that that’s when they recommissioned the 19th-century irrigation system.

N'arweet: Oh. So, they’ve gone back to the old way of looking at things? See, you’ve got to understand the past to inform the future. That’s good.

Ana: That’s why it’s so interesting to see that waterway.

N'arweet: Obviously, it continues to live. That’s probably very good. So, you had to go back to look at the way things were. That’s interesting. So, the past is informing you for the future.

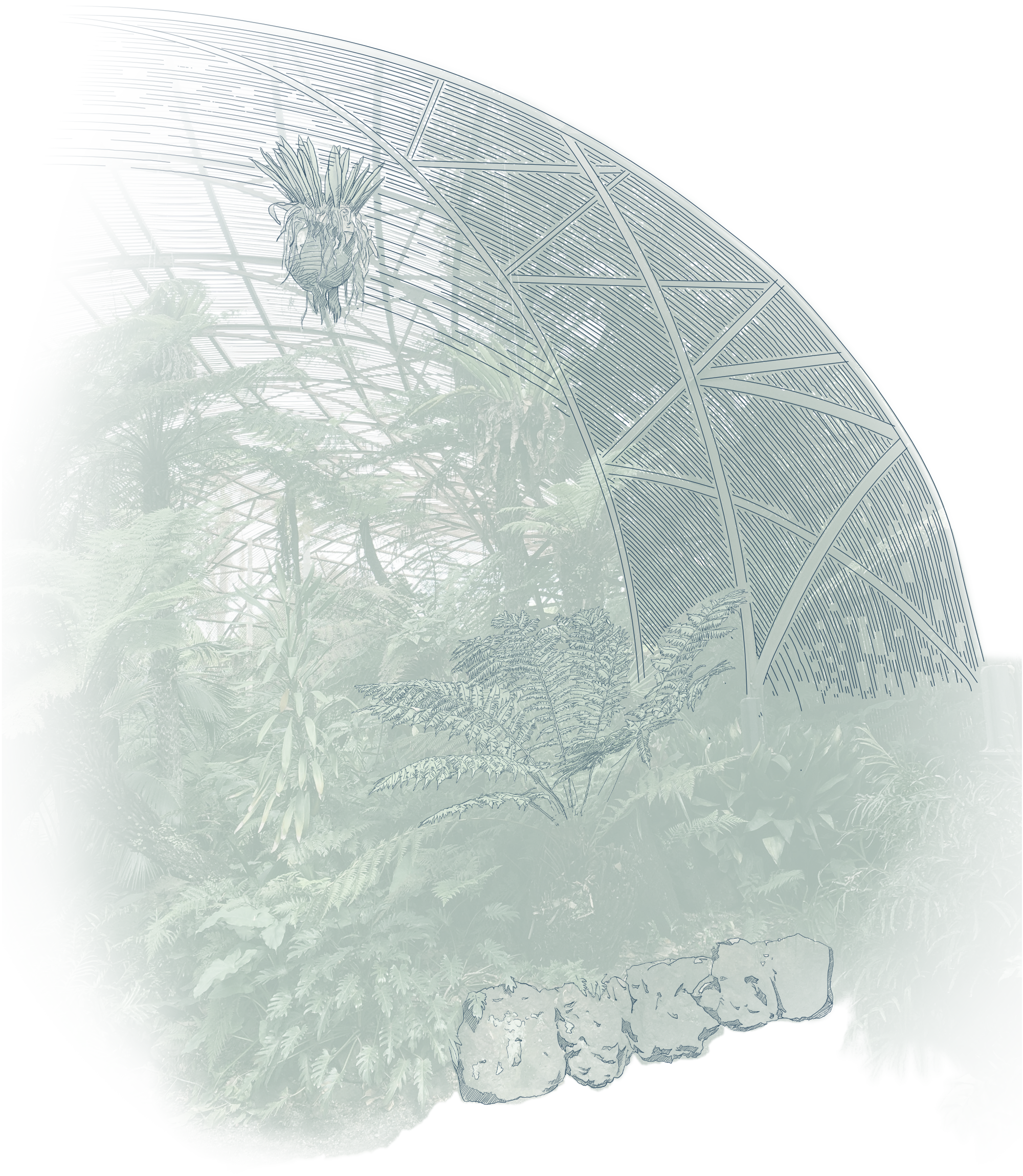

Ana: Isn’t this fernery a beautiful place? When visited at different times of the day the light, the sounds, the smells evoke landscapes that we know, that we can imagine have continued throughout deep time. You can hear the birds at dawn, and you can hear the frogs croaking when the sun goes down. Was this how the landscape at Rippon Lea looked before European settlement? Definitely not! This beautiful sheltered garden has been carefully planted and designed to allow the ferns to flourish. The vaulted wooden shading structure protects from sunlight, much as the old growth eucalypts do in the Dandenong ranges not far from here; the sunken landscape means the fernery is cooler than the garden around it; and the water pumped up from the underground provides the fernery with a continuous flow which keeps it moist and lush. If you are lucky, you might hear or see an eel, slipping and gliding through the water channels, or in the pools at the base of the waterfall. You can even imagine the eels as they travel below us through the underground pipes as they make their way through stormwater drains to the lake and the bay. It is all interconnected.

Soon after the National Trust took over the management of Rippon Lea, the severe Eastern Australian drought, and subsequent water restrictions of the 1980’s threatened the garden and the ecosystems that it supports. The National Trust had to think laterally to find a viable method to support the garden. But instead of looking towards new ideas of sustainability and innovative technologies of the 1980’s, they looked to the past – to a sustainable underground water system that was installed in the 1860’s and which nurtured this garden before mains water existed.

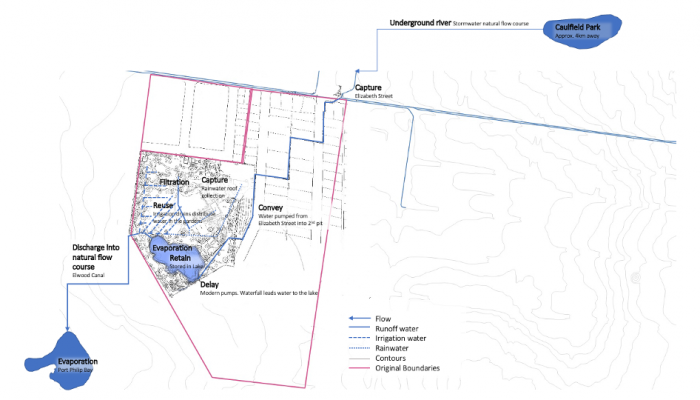

The water infrastructure that supports the Rippon Lea garden was designed and installed by Friedrick Sargood and his gardener Anderson in the 1860’s, who conceived of the house and landscape and the water infrastructure as a connected system. Around this time, the nearby Paddy’s Swamp, a wetland fed by a naturally occuring spring,was altered, reduced in size and drained into a tunnel which travelled underneath the streets of Elstenwick and down Glen Eira Road. The first design for the water drainage system at Rippon Lea tapped into this drain at the junction of Elizabeth Street and Glen Eira Road. The water would enter a pit that then gravity-fed through a 9-inch diameter glazed clay pipe to a brick well within the property. A windmill would pump the water up from the tunnel 9m below ground to a pipe that fed directly into the Lake. Although used for ornamental and leisure value, the lake was designed to act as an enormous water storage device, capturing water that can later be used to irrigate the garden.

Stormwater runoff is also integrated into the system at Rippon Lea – water is collected from the roof of the house and travels through the pipes to the Lake. From there, the water is pumped through the irrigation system (map 2) across the grounds in a series of pits and clay pipes that you can still see and hear beneath your feet. The pits are quite visible, you just need to walk around and look closely, there are 83 of them. An extensive network of subterranean drains carries subsoil water from the site, as well as overflow from the lake, directly into the railway cutting before it re-enters the Byron drain system and goes out to the Bay. The Rippon Lea irrigation system was conceived as a closely integrated water management system that fully used on and off-site water, making the Estate almost totally self-sufficient in its water requirements.

The reticulated system at Rippon lea can be considered as ‘water sensitive’: it contributes to more sustainable flood management by storing stormwater on site which would otherwise enter the drainage system during heavy rains; and it captures naturally occurring water flows including the underground spring water and runoff from the house and grounds to irrigate the garden through self-sufficient means. Water at Rippon Lea is available all year round, enabling the site to support ecosystems such as the fernery and to promote a thriving biodiversity of plants, insects and animals.

In 2018, the Glen Eira Biodiversity study designated Rippon Lea as a ‘biodiversity hotspot’. The study detected 14 wild and local plant species including seven native water plants which were not recorded anywhere else in the study. An incredible array of birdlife was also recorded, and this list has been added to by naturalist Gio Fitzpatrick who has observed up to 40 species of native birds in his regular visits to Rippon Lea garden. Gio describes how Rippon Lea has become a haven for birds whose numbers have dramatically decreased in urban Melbourne in recent years: small bush birds such as Brown Thornbills, Silvereyes, Spotted Pardalotes and Grey Fantails; water birds such as Nankeen Night Herons; and even birds of prey such as the collared sparrowhawk. Gio credits the complexity of the low and mid storey growth for creating a protective habitat for small birds, which in turn attract larger birds of prey.

The study also significantly registered the presence of the Shortfin Eel, a species which again was not observed anywhere else in Glen Eira. Shortfin eels are born in the Coral Sea near New Caledonia and then swim thousands of kilometres from saltwater to freshwater. At Rippon Lea, the Eels most likely swim up the Elster canal (500m away) and from there negotiate the complex network of underground drains and pipes until they reach the lake. This journey is all the more impressive on the way back, when the eels have matured to their full size.

The aim of the National Trust is to ‘conserve and protect our heritage for future generations to enjoy.’ At Rippon Lea, these acts of conservation and protection extend perhaps most importantly to the nurturing of local plants, animals and insects threatened by the urbanisation of the surrounding landscape. The underground water at Rippon Lea plays an integral role.

Ana: Yep. Probably birds.

N'arweet: Birds? Of course, birds. You know, birds – frogs?Because that will tell you how healthy the environment is. We should listen. That makes sense of the health and wellbeing of the environment too. It’s an indicator.

Ana: Maybe turtles.

N'arweet: They were having a go at different sort of ecology here, aren’t they? No wonder people like coming here. I can smell the freshness and the birds, the night birds. They probably have little possums I suppose.

I think this is a magnificent place. And It’s that sort of thing that I’m constantly puzzling over and constantly trying to make sense of these beautiful estates like this.

I’m now looking at it with a different view now. It’s different. It’s beautiful. Serves its purpose for this place. But I want to ensure that it serves the purpose of the planting and nature, you know?

Get down and be active and look after Country. Don't talk about it. Care for her. Look after her. Celebrate her. Celebrate all the gifts that you've been given.

References

Fitzpatrick, Gio. 2018. “Birds in Parks: A Bird’s Ear View of Rippon Lea.” Wild (blog). September 24, 2018. https://wild.com.au/people/rippon-lea-birds-ear-view/.

Lorimer, Graeme S. 2018. “Biodiversity in Glen Eira.” Version 1.1. City of Glen Eira: Glen Eira City Council. https://www.gleneira.vic.gov.au/media/3008/biodiversity-in-glen-eira-2018.pdf.

Discover Rippon Lea.

See what hides beneath

Rippon Lea House and Gardens

Rippon Lea House and Gardens