Being on Country

In this series of three audio-visual essays, researcher Ana Lara Heyns shares things she has learnt about the water landscape around Rippon Lea through walking and yarning with Boon Wurrung elder N’arweet Dr Carolyn Briggs AM, and through careful study of archival images, oral histories, maps, newspapers and diaries. In this essay, Ana considers the endurance of Indigenous people through colonisation, and N'arweet shares her journey to repair old memories by retracing the steps of her ancestor Louisa Briggs.

We've done a lot of actions for doing something and reclaiming that back. One of the recommendations was language, reclaiming our language. Also reclaiming our rights to have a voice that has been silenced. Our Elders, these voices were silent but we've been able to glean lots of the old records and our historical stories through our oral traditions and validating it with western material.

So I had to retrace my child in me. Retrace the memories. The deep memories of place.

A lot of my ancestors were moved from one place to another on missions and reserves. So the only thing they had was stories and memories. So I had to unpack those memories and follow their journey.

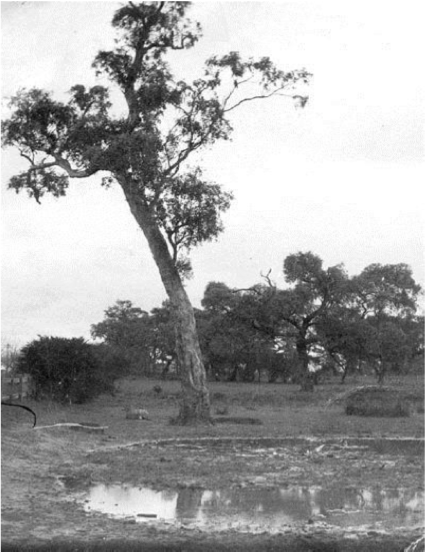

Ana: Walk along the lake with me, it’s such a beautiful body of water is such a constant presence in the landscape – it’s hard to imagine this lake did not exist before Rippon Lea was designed. How did that happen? We see the ducks and their ducklings dabbling, feeding on the rich variety of insects and aquatic plants scattered across this lake as if it has always existed. Different historical sources such as journals and diaries from colonial settlers, oral accounts of Indigenous people, photographs and topography, suggest that the area where the Rippon Lea lake sits was prone to inundation. Look at this old picture, it was taken during the early colonial years somewhere along Glen Eira Road, not too far from here. A tall river red gum sits on the edge of a low swampy water body, showing the ecology that was being replaced with urban development. Freidrick Sargood must have had a keen eye for the landscape, learning from observing the way water travelled and lay as he and his first head gardener excavated the land to turn a seasonal boggy area into an artificially created lake.

If we look carefully at the Rippon Lea Lake we can see something similar – two big old river red gum trunks, the trees long dead, but their roots still deep in the ground, under the lake. These trees pre-date the Rippon Lea estate and were integrated by Sargood into the garden design. Photos of the grounds show these trees through the decades, alive and well, towering over the landscape even in 1860, dying in the mid 20th century.

I’m taking a moment to contemplate these trunks, observing closely the marks on them. Are these scars made by people? Perhaps this one is a canoe mark! Archaeologist David Johnson from the Boon Wurrung Land and Sea Council thinks that these trees may hold the scars left after the making of a coolamon, a circular wooden bowl, or perhaps a raft canoe, a small watercraft used to carry tools, children or other good when walking in a watery landscape. Maybe hundreds of years before today this area was a seasonal swamp, and people used these river red gums to make tools, bowls and vessels. The tree trunks still hold their majestic form, proudly witnessing the time and water passing by. Spending some moments with these trunks I can only imagine the wisdom these trees hold.

Indigenous ways of knowing water are passed down through generations in aural tradition and stories. N’arweet tells the story of the Time of Chaos which has endured through time through her family. Long before the city that we know as Melbourne was built, N’arweet tells us, Port Phillip Bay was not filled with water – instead it was a large flat grassy plain. The Yarra river, or the Birrarrung meaning the river of mists, would flow out across this flat plain into the sea. N’arweet’s ancestors, as custodians of their land, traded and welcomed people from other clans of the Kulin Nation, and obeyed the laws of the creator, Bundjil. But one day, the clans were in conflict and they neglected their lands. The sea became angry and flooded the flat plain, covering the land and the rivers that flowed through it. This flooded area became the body of water we now call Port Phillip Bay.

In 2011, carbon dating corroborated this story using core samples of the seafloor, and imagery of the meandering river-like channels that still flow on the floor of Port Phillip Bay. Their research suggests that Port Phillip Bay was dry between ~2800 and 1000 ago (Holdgate et al, 2011). It is humbling to consider the careful passing of this story through generations over thousands of years which allows us to learn from it today.

N’arweet also shares the The Journey of the Iilk which tells us about the annual migration of the shortfin eel. Eels are born thousands of kilometres away in the Coral Sea off northern Australia. They migrate south to the coasts of Australia when they are just tiny glass eels, and make their way up the freshwater tributaries to find warm, safe inland water bodies to live for 20 years or more before they return to the Coral Sea to reproduce and die. Indigenous people understood the cyclical journey of this amazing creature. The migration of the eels provided certainty – it represented the act of taking care of the land and the sea in perpetuity, providing prosperity for the population over centuries.

But there are many other stories and voices of Indigenous people that were lost – colonisation, and the processes of urbanisation which accompanied it had a devastating effect on their way of life. Indigenous people in the Melbourne area people faced dispossession of their lands, the effects of introduced illness and disease, violence and injustice. Urban ‘progress’ caused the pollution and draining of swamps, as well as the disconnection of people from waterways, and the resources that those waterways had once nurtured. Rippon Lea Estate is part of this process.

The disruption of cultural practices, and the violent removal of people from Country means that memory and knowledge have been interrupted and have to be repaired. N’arweet is a descendant of Louisa Briggs, a Boon Wurrung ancestor who was forcibly taken as a child with other Boon Wurrung women from their lands at Point Nepean and taken to the islands in the Bass Strait. Louisa survived and made her way back to Victoria looking for her people and her Country. N’arweet tells us of her journey to follow the footsteps of Louisa Briggs, and to repair cultural memory:

I found that Louisa, when she was coming back to country back in 1850s, '60s, she sung water songs to come back from that island.

So she obviously maintained that memory as a child, when she was taken with her mother and her grandmother to that island and how she could describe Melbourne before settlement.

So that's handed down. Songs are handed down. I didn’t realise until my cousins, they're 96 years old, but they still had the songs. I saw them as lullabies but they were songs that they grew up with from her. That my Nappa, her son, had maintained.

I think it's very clever that the eels can still find their way home. They'll always find their way home. It's like us. Just keep mapping. Keep mapping for water springs. We keep mapping for understanding how we read our land.

In 2017 the Biodiversity Report of the City of Glen Eira registered the presence of the shortfin eel in just one location: here at Rippon Lea’s Lake. The eels find their way through the stormwater drains and the intricate 1860’s clay pipe water pipes at Rippon Lea Estate. When you explore Rippon Lea, take a few minutes to contemplate by the lake, you might spot an eel or two. Consider the journey they have taken to be here and the journey they still have ahead of them. These eels embody the endurance of Country.

‘For me, the metaphor of the eel is quite powerful. It is a story that connects over time and place because what it talks to is the notion of resilience—resilience of Indigenous people, after 240 years, and their commitment to showcasing culture and connecting and maintaining relationships to Country.’ - Jeffa Greenaway, Indigenous Architect, 2019.

References

Briggs, Carolyn. The Journey Cycles of the Boonwurrung: Stories with Boonwurrung Language. 2nd Edition. Melbourne: Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages (VACL), 2014. 21

Briggs, Carolyn. n.d. “Boon Wurrung: The Filling of the Bay – The Time of Chaos.” Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages. https://cv.vic.gov.au/stories/aboriginal-culture/nyernila/boon-wurrung-the-filling-of-the-bay-the-time-of-chaos/.

Holdgate, G. R., B. Wagstaff, and S. J. Gallagher. 2011. “Did Port Phillip Bay Nearly Dry up between ∼2800 and 1000 Cal. Yr BP? Bay Floor Channelling Evidence, Seismic and Core Dating.” Australian Journal of Earth Sciences 58 (2): 157–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/08120099.2011.546429.

“The Water Story — A Conversation between Jefa Greenaway and Samantha Comte.” 2019. Potter Museum of Art (blog). July 7, 2019. https://art-museum.unimelb.edu.au/resources/articles/the-water-story-a-conversation-between-jefa-greenaway-and-samantha-comte.

Lorimer, Graeme S. 2018. “Biodiversity in Glen Eira.” Version 1.1. City of Glen Eira: Glen Eira City Council. https://www.gleneira.vic.gov.au/media/3008/biodiversity-in-glen-eira-2018.pdf.

Discover Rippon Lea.

See what hides beneath

Rippon Lea House and Gardens

Rippon Lea House and Gardens